When Zarr Stopped Being a File Format: Notes from my first weeks at Development Seed!

Table of Contents

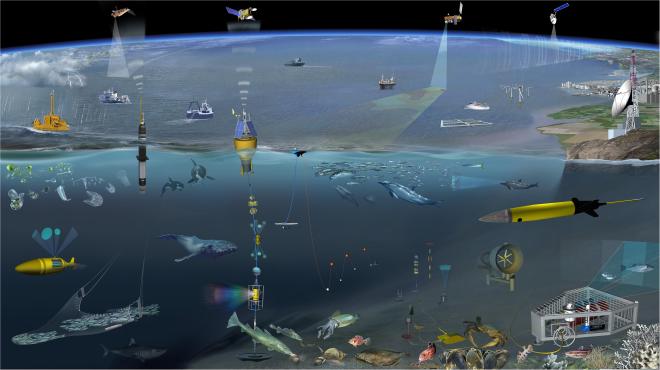

For a big part of my career, I built data processing systems for oceanographic observations. I designed pipelines that ingested data from underwater buoys, research vessels, and satellite instruments. Working with observational data at scale, I developed strong opinions about data formats. NetCDF became my default because it is a robust, well-documented format that handles multi-dimensional scientific arrays with complete metadata.

So when I transitioned to cloud engineering and started working with Earth observation data infrastructure, I made what seemed like a reasonable assumption: Zarr would be NetCDF for the cloud. Same conceptual model, just optimized for object storage instead of POSIX filesystems.

That assumption lasted about a week 😅

What Actually Happened #

I started my Zarr learning with Lindsey Nield’s excellent explainer “What is Zarr?” on the Earthmover blog. It’s a really nice introduction, very well written, that presents all the key points about Zarr. The article compared Zarr to other file formats, talked about chunks and compression, showed storage layouts. It all made sense on paper, but something in my understanding was still missing. I couldn’t quite connect the technical details to why everyone seemed so enthusiastic about it.

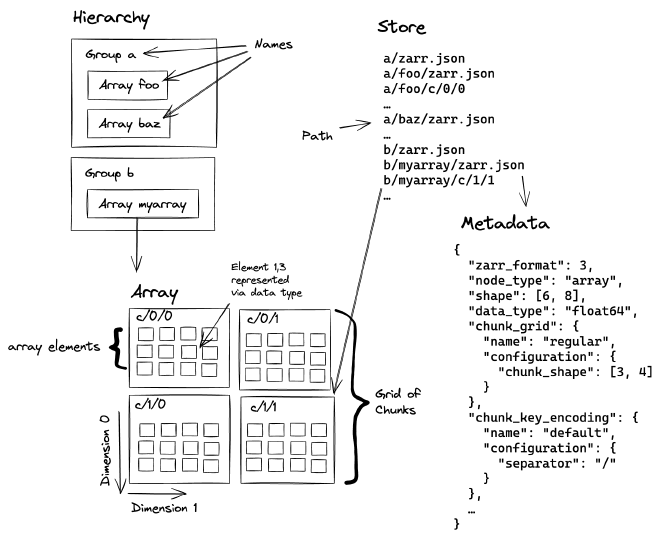

Then I read Davis Bennett’s presentation from the resources published in the 2025 Zarr Summit recap. In his talk “What is Zarr (and what isn’t it)”, Davis explains something that reframed completely how I understood Zarr: Zarr is an API or protocol, not a conventional file format. For my scientist friends who are struggling in grasping the meaning of an API, it can be summarized as a set of rules and definitions that let software systems communicate with each other.

I had been approaching Zarr like it was a container format with some clever cloud optimizations. But I had been missing the point… Zarr is fundamentally about storing arrays as collections of named chunks. Each chunk gets a unique identifier (a key), and when you request specific data, for example, reading a time slice or spatial subset,Zarr figures out which chunk keys to fetch. It doesn’t care where those chunks actually live. The keys can point to files on disk, objects in cloud object storage, or entries in a database.

This is an important distinction compared to traditional file formats, and it completely changed how I think about designing data pipelines.

An Oceanographic Sensor Network Analogy #

In my oceanographic work, we operated networks of underwater instruments. Autonomous gliders, moored buoys, profiling floats, each collecting continuous measurements. When analysing large amount of data, I learned quickly that “download everything first, then analyze” doesn’t scale well. At that time I wished there was an efficient way to support selective queries (give me temperature profiles between these dates at these depths), lazy evaluation (don’t fetch data you won’t use), distributed access (multiple researchers querying different aspects simultaneously), and partial reads (get monthly averages at a specific location without downloading daily samples of an entire region).

Zarr’s key-value architecture enables exactly these patterns for array data.

Different Ways to Access Data #

Working through one of the EOPF tutorial on Zarr (Earth Observation Processing Framework) changed how I was thinking about the problem. The tutorial shows different ways to access the same Sentinel-1 radar data stored in Zarr format. At first this felt like API complexity. Then I realized each pattern represents a different mental model, and both are equally valid depending on your workflow.

Here’s the first approach, opening the entire hierarchical structure:

import xarray as xr

# Open the complete data tree

dt = xr.open_datatree(url, engine='zarr', chunks={})

This gives you the full organizational structure. Groups, subgroups, the whole hierarchy. It’s exploratory. You’re getting oriented in unfamiliar data. In NetCDF terms, this would be like opening a file and running ncdump -h to see what variables exist and how they’re organized.

The second approach jumps directly to a specific group. You can do it in two different ways:

# Access a specific measurement group directly

ds = xr.open_dataset(

url,

engine='zarr',

group='measurements/VV',

chunks={}

)

or

# Navigate to a group, then convert to a dataset

ds = dt["measurements/VV"].to_dataset()

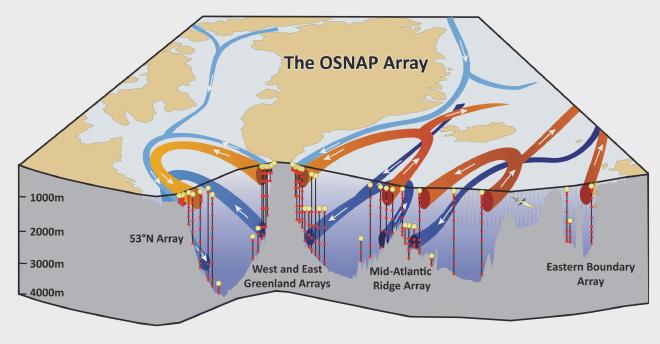

You already know what you want. You know the data structure. Just get that specific variable without loading anything else. This is the “I have worked with this dataset before” pattern. In my OSNAP mooring array processing, this would be equivalent to querying just the current meter data from a specific mooring location without pulling temperature and salinity measurements from all the other moorings across the North Atlantic.

Something crucial about how both of these are accessing data: there is no download step, it is over HTTP from a remote URL. No local caching is needed before you start working. Zarr figures out which chunks to fetch based on what you are actually requesting.

The chunks={} parameter preserves the original chunking from the metadata. The idea behind it is to respect the intent of whoever organized the data. They chose those chunk dimensions for a reason, probably based on common access patterns, and using chunks={} means “trust those decisions”.

Chunks as Architecture, Not Optimization #

In NetCDF, chunks are a performance tuning option. You can use them to optimize read patterns, or you can ignore them entirely. The format still works.

In Zarr, chunks define the data structure itself. Davis’s other presentation makes this clear: Zarr stores large arrays as separate sub-arrays. Each chunk is an independent unit that can be read, written, or compressed separately. The format is lazy: it only creates data chunks when values are written.

This maps very well to distributed scientific workflows. When I was processing data from the OSNAP mooring array, we didn’t collect uniform spatial grids across the North Atlantic. We had moorings at specific locations spanning from Labrador to Scotland, each equipped with multiple instruments at different depths measuring temperature, salinity, and velocity. Each mooring was its own data unit, each sensor type its own stream. The observational data was inherently chunked by location, by instrument, by depth.

Zarr formalizes this approach. Chunks themselves become the fundamental units and the chunking strategy can become an expression of your data’s structure and your access patterns.

What This Changes #

The remote access pattern from the EOPF tutorials reflects how Zarr fundamentally works. You point to a URL, describe what you want, and the system fetches the relevant chunks. There is no need to download the data before running a processing workflow, or manage local copies of the data.

For Earth observation workflows, this matters a lot! Satellite data archives are massive. A single Sentinel-1 scene can be gigabytes but an analysis might only need a specific polarization, a particular time range, and/or a subset of the spatial extent. Similarly, climate model outputs can be terabytes spanning decades of simulations across global grids. A researcher studying regional precipitation patterns doesn’t need global temperature data at every vertical level! While NetCDF-4 with OPeNDAP servers can enable remote subsetting, it requires specialized server infrastructure and sequential access patterns. Zarr makes this pattern native and works directly with standard object storage over HTTP. You fetch only the chunks that matter for your specific query, no special middleware is required. Plus, Zarr’s independent chunks enable parallel reads, which means multiple chunks can be fetched simultaneously, dramatically improving performance compared to OPenNDAP’s sequential file access!

I think that is why everyone building cloud-native geospatial infrastructure is converging on Zarr. It provides both a performance gain and a better underlying data model to work with Earth observation data.

What I’m Still Learning #

I am in my 2nd week into understanding Zarr, and there is still plenty I don’t fully grasp! The differences between Zarr V2 and V3, differences between Zarr and GeoZarr, differences between Zarr conventions and Zarr extensions and how they relate to the core specification, or details of chunk encoding and compression options. But the fundamental mental model shift has happened: I have stopped thinking about files and have started thinking about array protocols over key-value stores.

If you are coming from NetCDF, this requires unlearning some assumptions (file handles, sequential reads, monolithic containers). These concepts don’t map cleanly to Zarr because I think Zarr isn’t trying to be a better file format but it operates on different principles.

In my opinion, this difference should matter for scientists and data engineers building systems to handle large-scale Earth observation. There is definitely a learning curve, but I think the mental model shift is worth it, especially as Zarr is becoming one of the data standard to work with climate data at the Exascale.